Development Projects

This page lists some of our development projects where old hardware meets modern

computer equipment. All projects are selfmade, with partly enormous hardware and

software efforts, like routed PCBs, kernel drivers and microcontrollers.

Paper tape processing with contemporary computers

We were often in a situation when some data stored on a punched paper needed

to be sent over long distances. Having Internet access and e-mail, that's no matter

for todays computers, once you can read in paper tapes. The other way around,

punching new or modified data on punched papers is also a frequent need in our daily

business.

Therefore we initiated the Paper Tape Project, having the

pronounced goal to handle paper tapes with contemporary computers, that is, to

read, change and write (punch) them.

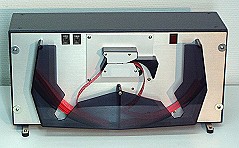

We use comparatively new punched paper devices that already feature a Centronics interface at TTL level. Unfortunately the devices (in detail: reader Ghilmetti FER 201, puncher FACIT 4070) didn't yet implement the Centronics common standard from the 1970s (officially standardized as IEEE-1284 not until 1994), therefore simply connecting those devices with a standard parallel port printer cable won't do the job.

Ghilmetti FER 201 reader with framework for reading zig-zag tapes

The very first step was to read the manual carefully to assemble a specially wired cable to connect the punch card device with the parallel port of a PC (commonly known as "LPT port", a standard port on PC motherboards just a few years ago). Since the devices don't implement the standarized hand shake, the second step was to implement a suitable driver to emulate the right communication behaviour for the punch card devices.

Development started on the free GNU/Linux Operating System where we used the ppdev framework of the Linux 2.6 kernel series to program a user space driver in the programming language C with a little effort compared to a real kernel space driver.

The legendary puncher FACIT 4070

The parallel port consists of three 8-bit hardware registers: a bidirectional data

register, a control register and a signal register. Since paper tapes are made of

8-bit words (octetts), we just connected these eight bits on the data register to save

them directly to one byte in the computer. Using the control and signal pins, we could

implement a interrupt (device cycle) driven communication, since the status register

features one interrupt enabled bit (strobe). Our devices punch at 80 chars/sec and read in

250 chars/sec, so even older PCs can easily run the driver programs.

As already told, there's not really the question how to model punched papers on

computers, since they use the same word length (8 bit) and computer files are

conceptually the same as paper tapes: byte arrays. A 250 byte binary file therefore

represents a 250 chars long punched paper. Thus processing punch card files

with Unix command line tools or hex editors is very easy. To speed up the workflow,

we wrote some simple perl scripts to label paper tapes. Afterwards we wrote a

graphical editor, called "Paper Tape Editor", where binary files could be visualized

and directly edited as paper tapes on the screen. This program was written in C, using

the Gtk+ toolkit. After writing drivers for the Microsoft Windows Operating System,

this program was extended to the "Paper Tape Suite" to read, edit, save and punch

paper tapes graphically. That way every possible procedures with paper tapes can be

performed with ordinary PCs.

You can get further details with a lot of documentation material on the homepage of The Paper Tape Project. The source code was released as open source can be checked out from the technikum29.de subversion repository.

Reading punch cards with contemprary computers

There is an historical storage media that is even more important than paper tapes: Punch cards. They were the one of the pillars of early mass electronic data processing and were used for saving data and program executables. Based on the Paper Tape Project, we started the Punch Card Project with the similar target of reading, editing and punching punch cards.

When connecting these small paper tape devices (shown above) directly to modern

personal computers via the parallel port ("LPT"), we noticed they were too slow for

communication. Having modern GHz powered high end computers, how's that possible?

The real cause for this performance is the software and hardware design of

contemporary personal computers. They are conceptually designed for processing huge

amounts of data and high speed calculations, but no more for short latencies with I/O

handling. Actually, all time-ciritcal parts in modern high speed communication

protocols (like USB, Ethernet, Firewire, etc.) are implemented in hardware. Software,

on the other side, features more and more abstraction levels, so there's no more

real-time operation even at kernel space.

There are real-time operating systems, indeed, but by using such an operating

system, the computer would be dedicated to communicating to the device. This is not

neccessary. There is a (not even young) branch of computers which perfectly match

all the criteria mentioned: Low latency, fast I/O, fully deterministic. Microcontroller

are these low cost processors, a single chip featuring a lot of peripheral equipment.

Documation M200 card reader (this one implemented by WANG)

We are using an ATmega microcontroller made by Atmel AVR. Most of the 40 digital I/O pins are directly wired to the electrical Input/Output of the punch card device Documation M200 (featuring a pneumatic card feed). On the other side of the small development board there is the RS232 port ("serial port"), communicating to the computer. This small board is actually so small that it fits right into the device's cabinet. Running with 8 MHz, the microcontroller is easily capable of hard real-time communication (300 cards/minute) and serving 4kB RAM, there is enough space for buffering a lot of punch cards until they can be sent to the virtually lazy computer via RS232. This is a quite old industry standard for serial data transportation, but since its very easy and robust, RS232 is quite perfect for such an interface. Using contemporary USB was no option since it's very complex and bulky (above all, there are cheap RS232-to-USB interfaces).

We wrote a program for the microcontroller that implements the device driver to the

punch card device. Now having an electrically specified interface to the computer (RS232),

how should we communicate to the computer (automatically)? Furthermore, in which way

should we represent a punch card with binary digits (zeros and ones)?

While modeling 8 bit paper tapes into 8 bit bytes is trivial, a punch card, having

80 columns with 12 rows each, is much more complex. Therefore we wrote the

PC Documation M200 µC Serial Communication Protocol that defines the

way how computer and microcontroller shall communicate autonomously. It defines, that

two punch card columns shall be packed into three octetts, each. This binary format has

been proposed by the computer sciencist Douglas

W. Jones.

For the computer side, we wrote the Punch Card Editor, a program that recieves

the punch cards from the microcontroller (via the RS232 interface) and visualizes them in

the graphical user interface. At this step, the text encodings (IBM H9 code, Bull Code)

can be used to translate between binary punch card data and ASCII text. Thus card decks

can be read in, modified and saved as files. Of course the comfortable program already

has the interface for punching paper tapes, once we have selected a device and programmed

some microcontroller for that job. At this point, there is also another benefit of this

approach: The program runs on all modern platforms/operating systems (like Microsoft

Windows, GNU/Linux, Apple OS X, etc. - there just needs to be some RS232 or USB connection).

You can get further details with a lot of documentation material on the homepage of The Punch Card Project. The source code was released as open source can be checked out from the technikum29.de subversion repository.